Today we will dive into OpenStack Keystone, the part of OpenStack that provides services like management of users, roles and projects, authentication and a service catalog to the other OpenStack components. We will first install Keystone and then take a closer look at each of these areas.

Installing Keystone

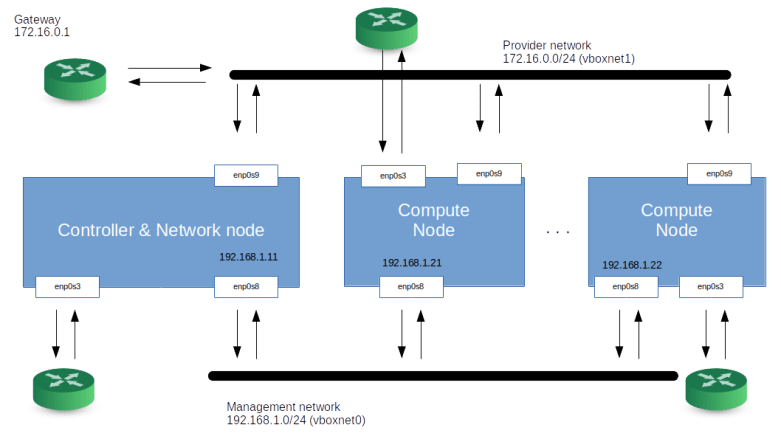

As in the previous lab, I have put together a couple of scripts that automatically install Keystone in a virtual environment. To run them, issue the following commands (assuming, of course, that you did go through the basic setup steps from the previous post to set up the environment)

pwd

# you should be in the directory into which

# you did clone the repository

cd openstack-samples/Lab2

vagrant up

ansible-playbook -i hosts.ini site.yaml

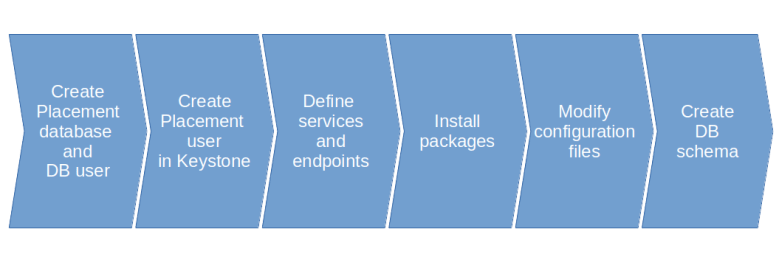

While the scripts are running, let us discuss the installation steps. First, we need to prepare the database. Keystone uses its own database schema called (well, you might guess …) keystone that needs to be added to the MariaDB instance. We will also have to create a new database user keystone with the necessary privileges on the keystone database.

Then, we install the Keystone packages via APT. This will put default configuration files into /etc/keystone which we need to adapt. Actually, there is only one change that we need to make at this point – we need to change the connection key to contain a proper connection string to reach our MariaDB with the database credentials just established.

Next, the keystone database needs to be created. To do this, we use the keystone-manage db_sync command that actually performs an upgrade of the Keystone DB schema to the latest version. We then again utilize the keystone-manage tool to create symmetric keys for the Fernet token mechanism and to encrypt credentials in the SQL backend.

Now we need to add a minimum set of domains, project and users to Keystone. Here, however, we face a chicken-and-egg problem. To be able to add a user, we need the authorization to do this, so we need a user, but there is no user yet.

There are two solutions to this problem. First, it is possible to define an admin token in the Keystone configuration file. When this token is used for a request, the entire authorization mechanism is bypassed, which we could use to create our initial admin user. This method, however, is a bit dangerous. The admin token is contained in the configuration file in clear text and never expires, so anyone who has access to the file can perform every action in Keystone and then OpenStack.

The second approach is to again the keystone-manage tool which has a command bootstrap which will access the database directly (more precisely, via the keystone code base) and will create a default domain, a default project, an admin user and three roles (admin, member, reader). The admin user is set up to have the admin role for the admin project and on system level. In addition, the bootstrap process will create a region and catalog entries for the identity services (we will discuss these terms later on).

Users, projects, roles and domains

Of course, users are the central object in Keystone. A user can either represent an actual human user or a service account which is used to define access rights for the OpenStack services with respect to other services.

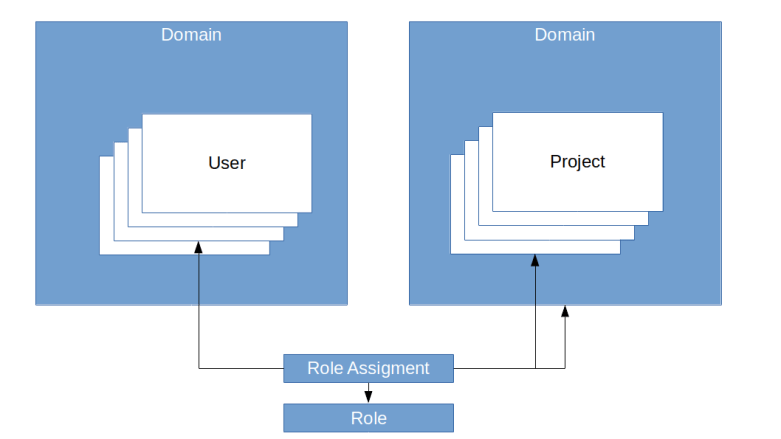

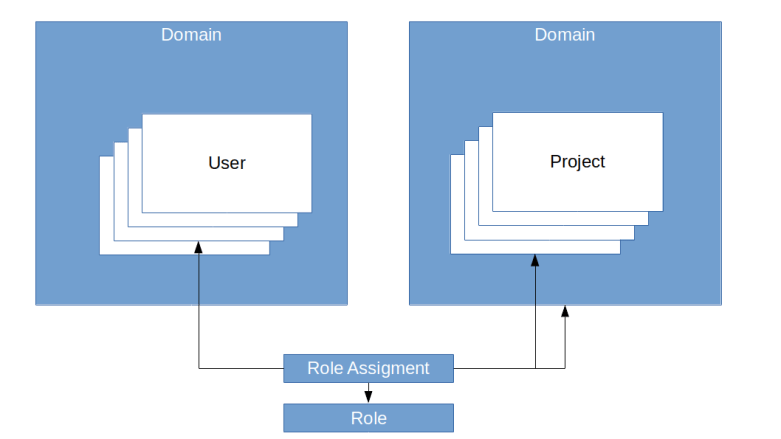

In a typical cloud environment, just having a global set of users, however, is not enough. Instead, you will typically have several organizations or tenants that use the same cloud platform, but require a certain degree of separation. In OpenStack, tenants are modeled as projects (even though the term tenant is sometimes used as well to refer to the same thing). Projects and users, in turn, are both grouped into domains.

To actually define which user has which access rights in the system, Keystone allows you to define roles and assign roles to users. In fact, when you assign a role, you always do this for a project or a domain. You would, for instance, assign the role reader to user bob for the project test or for a domain. So role assignments always refer to a user and either a role or a project.

Note that it is possible to assign a role to a user in a domain for a project living in a different domain (though you will probably have a good reason to do this).

In fact, the full picture is even a bit more complicated than this. First, roles can imply other roles. In the default installation, the admin role implies the member role, and the member role implies the reader role. Second, the above diagram suggests that a role is not part of a domain. This is true in most cases, but it is in fact possible to create domain-specific roles. These roles do not appear in a token and are therefore not directly relevant to authorization, but are intended to be used as prior roles to map domain specific role logic onto the overall role logic of an installation.

It is also not entirely true that roles always refer to either a domain or a project. In fact, Keystone allows for so-called system roles which are supposed to be used to restrict access to operations that are system wide, for instance the configuration of API endpoints.

Finally, there are also groups. Groups are just collections of users, and instead of assigning a role to a user, you can assign a role to a group which then effectively is valid for all users in that group.

And, yes, there are also subprojects.. but let us stop here, you see that the Keystone data structures are complicated and have been growing significantly over time.

To better understand the terms discussed so far, let us take a look at our sample installation. First, establish an SSH connection to some of the nodes, say the controller node.

vagrant ssh controller

On this node, we will use the OpenStack Python client to explore users, projects and domains. To run it, we will need credentials. When you work with the OpenStack CLI, there are several methods to supply credentials. The option we will use is to provide credentials in environment variables. To be able to quickly set up these variables, the installation script creates a bash script admin-openrc that sets these credentials. So let us source this script and then submit an OpenStack API request to list all existing users.

source admin-openrc

openstack user list

At this point, this should only give you one user – the admin user created during the installation process. To display more details for this user, you can use openstack user show admin, and you should obtain an output similar to the one below.

+---------------------+----------------------------------+

| Field | Value |

+---------------------+----------------------------------+

| domain_id | default |

| enabled | True |

| id | 67a4f789b4b0496cade832a492f7048f |

| name | admin |

| options | {} |

| password_expires_at | None |

+---------------------+----------------------------------+

We see that the user admin is part of the default domain, which is the standard domain used in OpenStack as long as no other domain is specified.

Let us now see which role assignments this user has. To do this, let us list all assigments for the user admin, using JSON output for better readability.

openstack role assignment list --user admin -f json

This will yield the following output.

[

{

"Role": "18307c8c97a34d799d965f38b5aecc37",

"User": "92f953a349304d48a989635b627e1cb3",

"Group": "",

"Project": "5b634876aa9a422c83591632a281ad59",

"Domain": "",

"System": "",

"Inherited": false

},

{

"Role": "18307c8c97a34d799d965f38b5aecc37",

"User": "92f953a349304d48a989635b627e1cb3",

"Group": "",

"Project": "",

"Domain": "",

"System": "all",

"Inherited": false

}

]

Here we see that there are two role assignments for this user. As the output only contains the UUIDs of the role and the project, we will have to list all projects and all roles to be able to interpret the output.

openstack project list

openstack role list

So we see that for both assignments, the role is the admin role. For the first assignment, the project is the admin project, and for the second assignment, there is no project (and no domain), but the system field is filled. Thus the first assignment assigns the admin role for the admin project to our user, whereas the second one assigns the admin role on system level.

So far, we have not specified anywhere what these roles actually imply. To understand how roles lead to authorizations, there are still two missing pieces. First, OpenStack has a concept of implied roles. These are roles that a user has which are implied by explicitly defined roles. To see implied roles in action, run

openstack implied role list

The resulting table will list the prior roles on the left and the implied role on the right. So we see that having the admin role implies to also have the member role, and having the member role in turn implies to also have the reader role.

The second concept that we have not touched upon are policies. Policies actually define what a user having a specific role is allowed to do. Whenever you submit an API request, this request targets a certain action. Actions more or less correspond to API endpoints, so an action could be “list all projects” or “create a user”. A policy defines a rule for this action which is evaluated to determine whether that request is allowed. A simple rule could be “user needs to have the admin role”, but the rule engine is rather powerful and we can define much more elaborated rules – more on this in the next post.

The important point to understand here is that policies are not defined by the admin via APIs, but are predefined either in the code or in specific policy files that are part of the configuration of each OpenStack service. Policies refer to roles by name, and it does not make sense to define and use a role that this is not referenced by policies (even though you can technically do this). Thus you will rarely need to create roles beyond the standard roles admin, member and reader unless you also change the policy files.

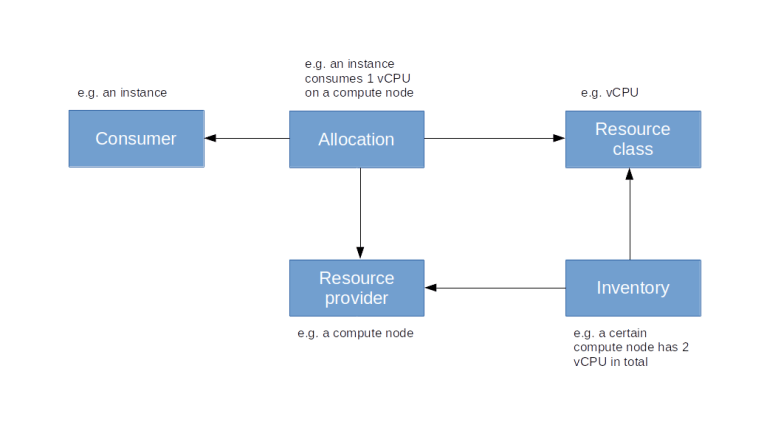

Service catalogs

Apart from managing users (the Identity part of Keystone), project, roles and domains (the Resources part of Keystone), Keystone also acts as a service registry. OpenStack services register themselves and their API endpoints with Keystone, and OpenStack clients can use this information to obtain the URL of service endpoints.

Let us take a look at the services that are currently registered with Keystone. This can be done by running the following commands on the controller.

source admin-openrc

openstack service list -f json

At this point in the installation, before installing any other OpenStack services, there is only one service – Keystone itself. The corresponding output is

[

{

"ID": "3acb257f823c4ecea6cf0a9e94ce67b9",

"Name": "keystone",

"Type": "identity"

},

]

We see that a service has a name which identifies the actual service, in addition to a type which defines the type of service delivered. Given the type of a service, we can now use Keystone to retrieve a list of service API endpoints. In our example, enter

openstack endpoint list --service identity -f json

which should yield the following output.

[

{

"ID": "062975c2758f4112b5d6568fe068aa6f",

"Region": "RegionOne",

"Service Name": "keystone",

"Service Type": "identity",

"Enabled": true,

"Interface": "public",

"URL": "http://controller:5000/v3/"

},

{

"ID": "207708ecb77e40e5abf9de28e4932913",

"Region": "RegionOne",

"Service Name": "keystone",

"Service Type": "identity",

"Enabled": true,

"Interface": "admin",

"URL": "http://controller:5000/v3/"

},

{

"ID": "781c147d02604f109eef1f55248f335c",

"Region": "RegionOne",

"Service Name": "keystone",

"Service Type": "identity",

"Enabled": true,

"Interface": "internal",

"URL": "http://controller:5000/v3/"

}

]

Here, we see that every service typically offers different types of endpoints. There are public endpoints, which are supposed to be reachable from an external network, internal endpoints for users in the internal network and admin endpoints for administrative access. This, however, is not enforced by Keystone but by the network layout you have chosen. In our simple test installation, all three endpoints for a service will be identical.

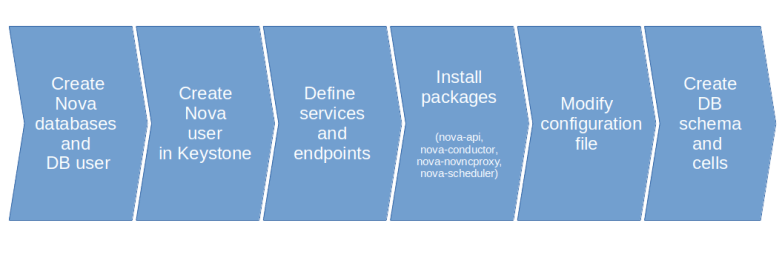

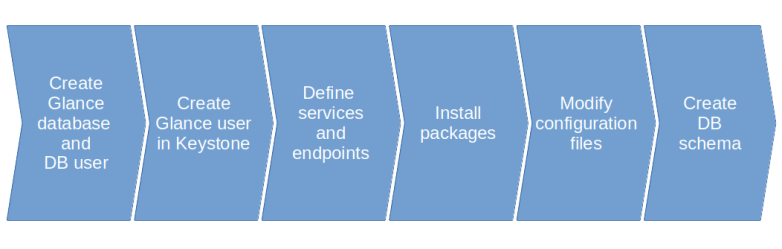

When we install more OpenStack services later, you will see that as part of this installation, we will always register a new service and corresponding endpoints with Keystone.

Token authorization

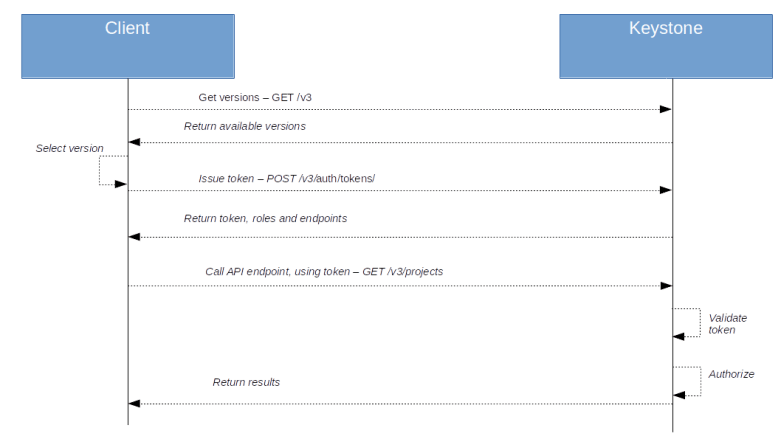

So far, we have not yet discussed how an OpenStack service actually authenticates a user. There are several ways to do this. First, you can authorize using passwords. When using the OpenStack CLI, for instance, you can put username and password into environment variables which will then be used to make API requests (for ease of use, the Ansible playbooks that we use to bring up our environment will create a file admin-openrc which you can source to set these variables and that we have already used in the examples above).

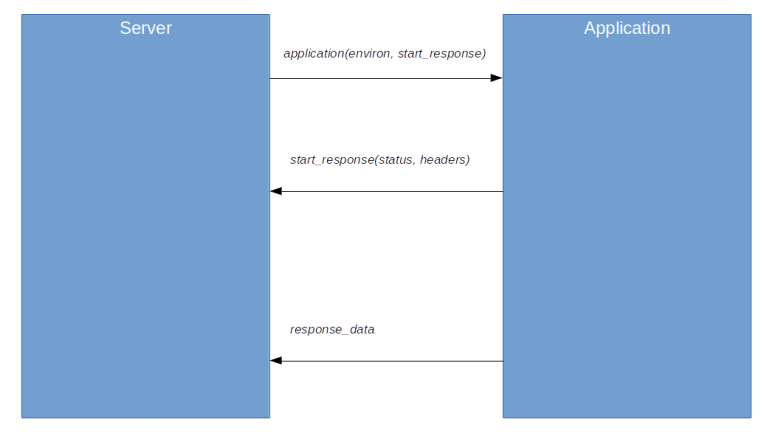

In most cases, however, subsequent authorizations will use a token. A token is essentially a short string which is issued once by Keystone and then put into the X-Auth-Token field in the HTTP header of subsequent requests. If a token is present, Keystone will validate this token and, if it is valid, be able to derive all informations it needs to authenticate the user and authorize a request.

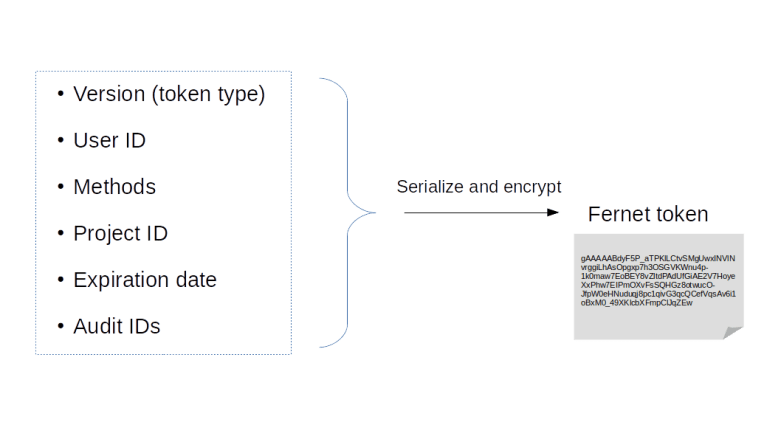

Keystone is able to use different token formats. The default token format with recent releases of Keystone is the Fernet token format.

It is important to understand that tokens are scoped objects. The scope of a token determines which roles are taken into account for the authorization process. If a token is project scoped, only those roles of a user that target a project are considered. If a token is domain scoped, only the roles that are defined on domain level are considered. And finally, a system scope token implies that only roles at system level are relevant for the authorization process.

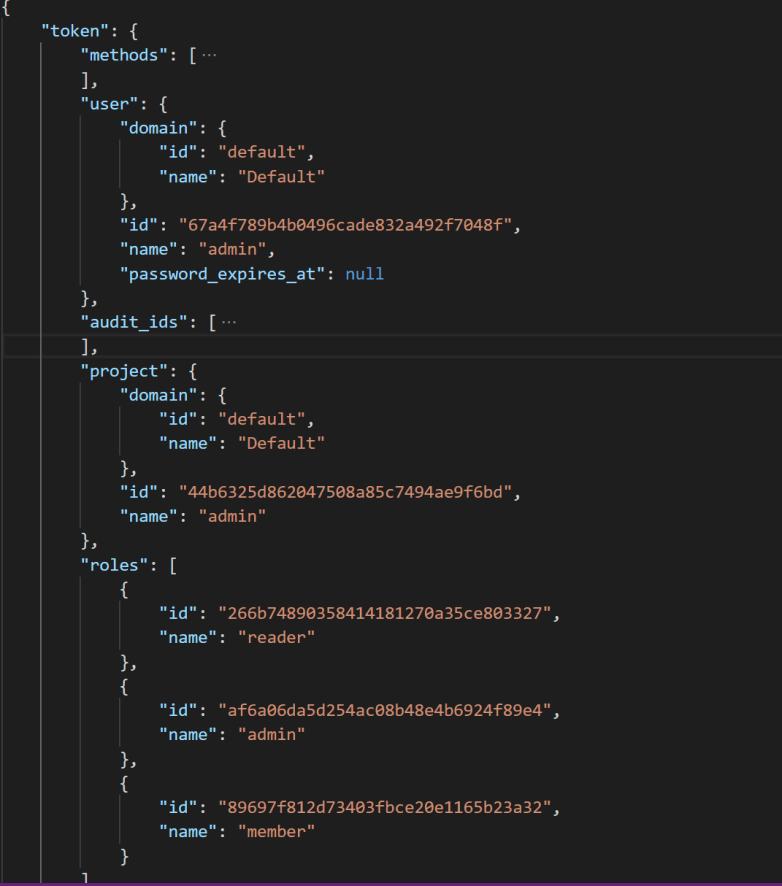

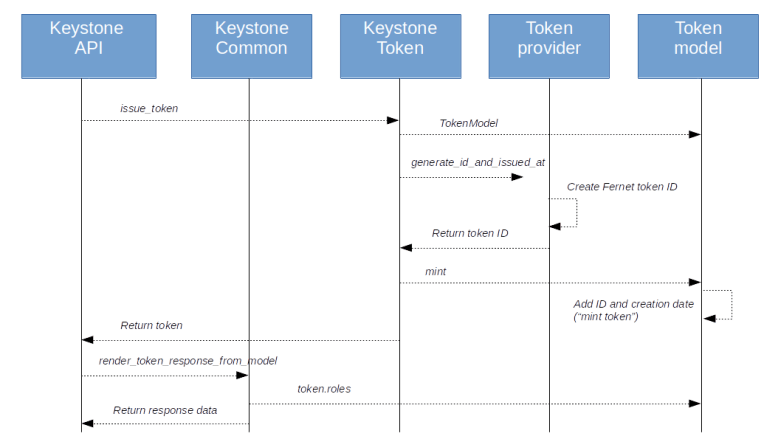

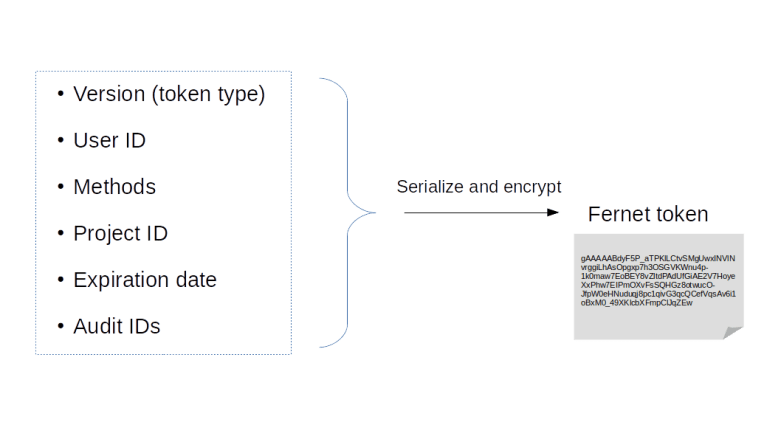

Earlier versions of Keystone supported a token type called PKI token that contained a large amount of information directly, including role information and service endpoints. The advantage of this approach was that once a token had been issued, it could be processed without any further access to Keystone. The disadvantage, however, was that the tokens generated in this way tended to be huge, and soon reached a point where they could no longer be put into a HTTP header. The Fernet token format handles things differently. A Fernet token is an encrypted token which contains only a limited amount of information. To use it, a service will, in most cases, need to run additional calls agains Keystone to retrieve additional data like roles and services. For a project scoped token, for instance, the following diagram displays the information that is stored in a token on the left hand side.

First, there is a version number which encodes the information on the scope of the token. Then, there is the ID of the user for whom the token is issued, the methods that the user has used to authenticate, the ID of the project for which the token is valid, and the expiration date. Finally, there is an audit ID which is simply a randomly generated string that can be put into logfiles (in contrast to the token itself, which should be kept secret) and can be used to trace the usage of this token. All these fields are serialized and encrypted using a symmetric key stored by Keystone, typically on disk. A domain scoped token contains a domain ID instead of the project ID and so forth.

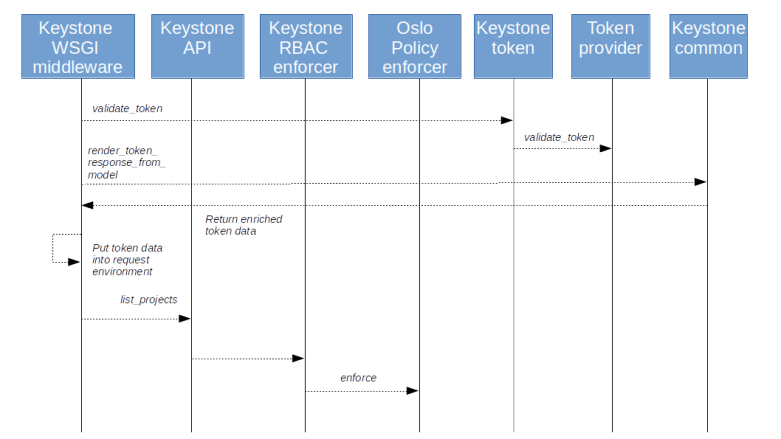

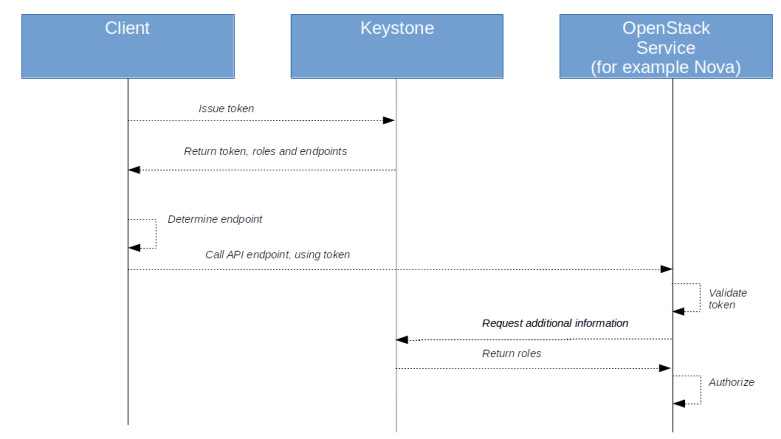

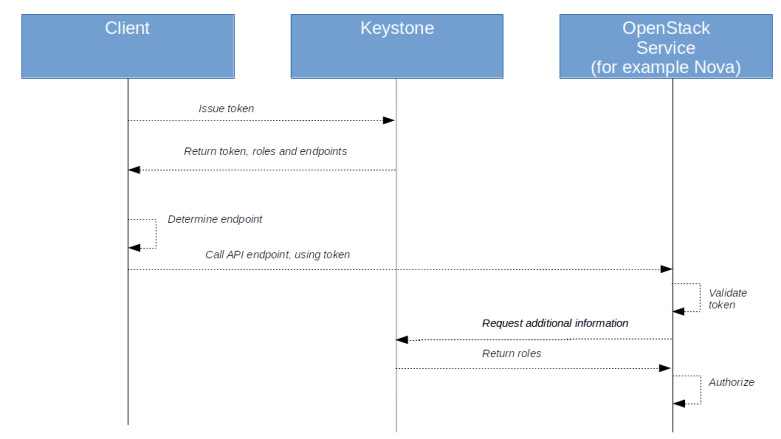

Equipped with this understanding, we can now take a look at the overall authorization process. Suppose a client wants to request an action via the API, say from Nova. First, the client would then use password-based authorization to obtain a token from Keystone. Keystone returns the token along with an enriched version containing roles and endpoints as well. The client would use the endpoint information to determine the URL of the Nova service. Using the token, it would then try to submit an API request to the Nova API.

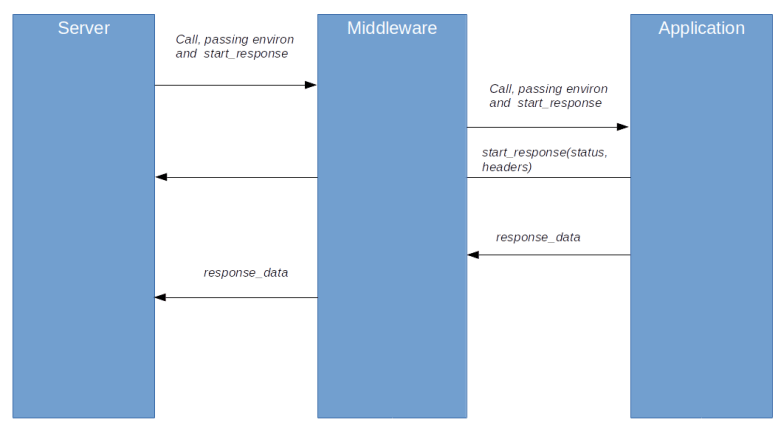

The Nova service will take the token, validate it and ask Keystone again to enrich the token, i.e to add the missing information on roles and endpoints (in fact, this happens in the Keystone middleware). It is then able to use the role information and its policies to determine whether the user is authorized for the request.

Using Keystone with LDAP and other authentication mechanisms

So far, we have stored user identities and group inside the MariaDB database, i.e. local. In most production setups, however, you will want to connect to an existing identity store, which is typically exposed via the LDAP protocol. Fortunately, Keystone can be integrated with LDAP. This integration is read-only, and Keystone will use LDAP for authentication, but still store projects, domains and role information in the MariaDB database.

When using this feature, you will have to add various data to the Keystone configuration file. First, of course, you need to add basic connectivity information like credentials, host and port so that Keystone can connect to an LDAP server. In addition, you need to define how the fields of a user entity in LDAP map onto the corresponding fields in Keystone. Optionally, TLS can be configured to secure the connection to an LDAP server.

In addition to LDAP, Keystone also supports a variety of alternative methods for authentication. First, Keystone supports federation, i.e. the ability to share authentication data between different identity providers. Typically, Keystone will act as a service provider, i.e. when a user tries to connect to Keystone, the user is redirected to an identity provider, authenticates with this provider and Keystone receives and accepts the user data from this provider. Keystone supports both the OpenID Connect and the SAML standard to exchange authentication data with an identity provider.

As an alternative mechanism, Keystone can delegate the process of authentication to the Apache webserver in which Keystone is running – this is called external authentication in Keystone. In this case, Apache will handle the authentication, using whatever mechanisms the administrator has configured in Apache, and pass the resulting user identity as part of the request context down to Keystone. Keystone will then look up this user in its backend and use it for further processing.

Finally, Keystone offers a mechanism called application credentials to allow applications to use the API on behalf of a Keystone user without having to reveal the users password to the application. In this scenario, a user creates an application credential, passing in a secret and (optionally) a subset of roles and endpoints to which the credential grants access. Keystone will then create a credential and pass its ID back to the user. The user can then store the credential ID and the secret in the applications configuration. When the application wants to access an OpenStack service, it uses a POST request on the /auth/tokens endpoint to request a token, and Keystone will generate a token that the application can use to connect to OpenStack services.

This completes our post today. Before moving on to install additional services like Placement, Glance and Nova, we will – in the next post – go on a guided tour through a part of the Keystone source code to see how tokens and policies work under the hood.