In this post, we will investigate the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, which is still one of the most popular algorithms in the field of Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, even though its first appearence (see [1]) happened in 1953, more than 60 years in the past. It does for instance appear on the CiSe top ten list of the most important algorithms of the 20th century (I got this and the link from this post on WordPress).

Before we get into the algorithm, let us once more state the problem that the algorithm is trying to solve. Suppose you are given a probability distribution on some state space X (most often this will be a real euclidian space on which you can do floating point arithmetic). You might want to imagine the state space as describing possible states of a physical system, like spin configurations in a ferromagnetic medium similar to what we looked at in my post on the Ising model. The distribution

then describes the probability for the system to be in a specific state. You then have some quantity, given as a function f on the state space. Theoretically, this is a quantity that you can calculate for each individual state. In most applications, however, you will never be able to observe an individual state. Instead, you will observe an average, weighted by the probability of occurence. In other words, you observe the expectation value

of the quantity f. Thus to make a prediction that can be verified or falsified by an observation, you will have to calculate integrals of this type.

Now, in practice, this can be very hard. One issue is that in order to naively calculate the integral, you would have to transverse the entire state space, which is not feasible for most realistic problems as this tends to be a very high dimensional space. Closely related to this is a second problem. Remember, for instance, that a typical distribution like the Boltzmann distribution is given by

The term in the numerator is comparatively easy to calculate. However, the term in the denominator is the partition function, and is itself an integral over the state space! This makes even the calculation of for a single point in the state space intractable.

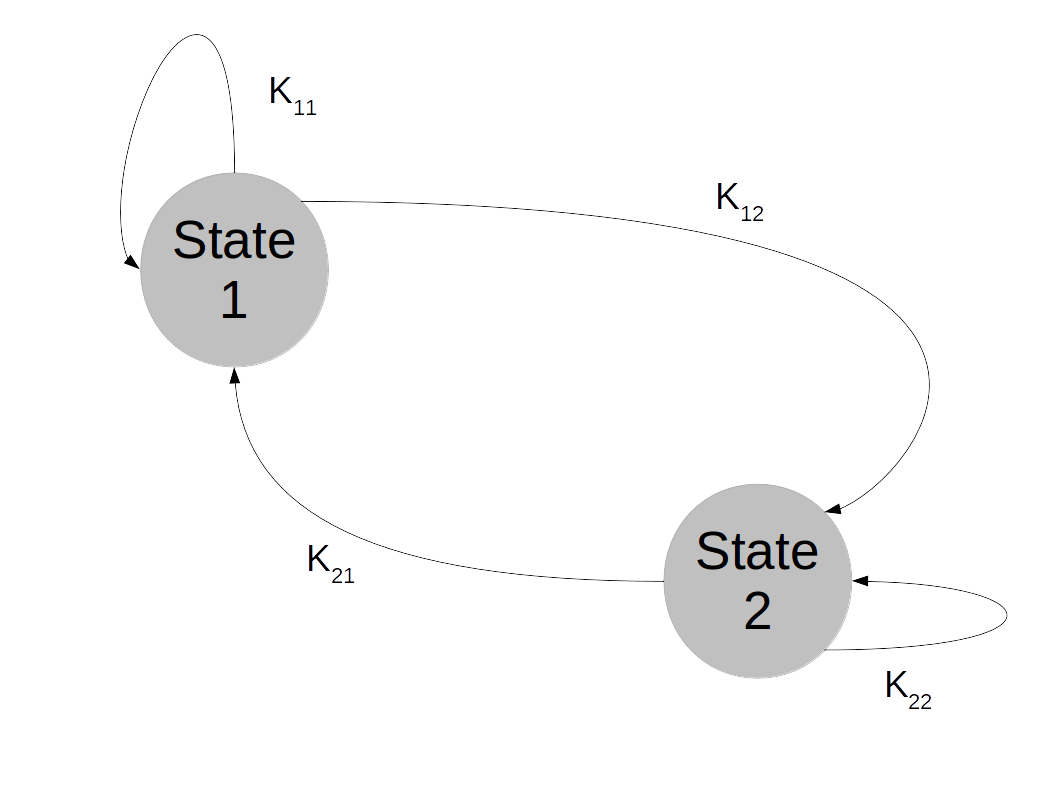

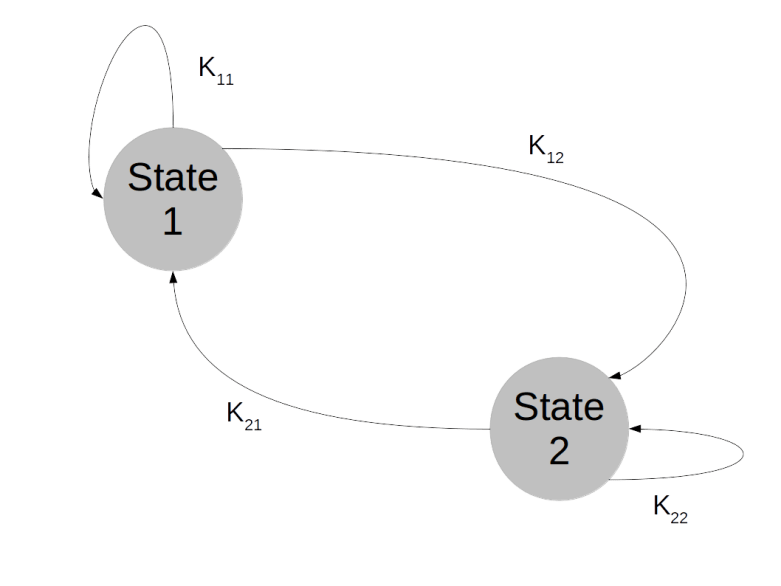

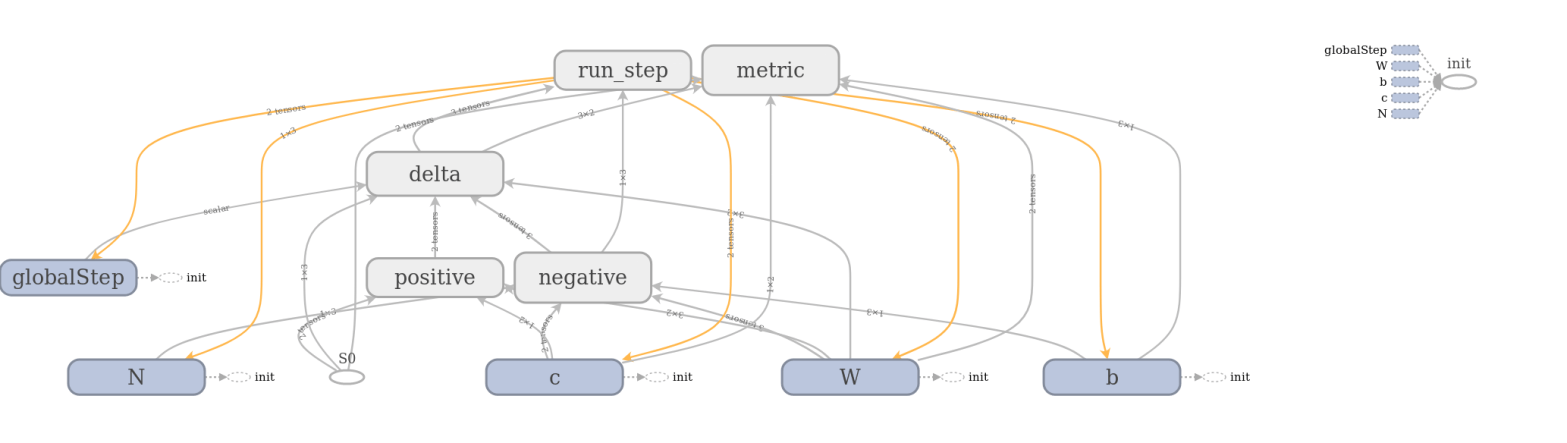

But there is hope – even though calculating the values of for one point might be impossible, in a distribution like this, calculating ratios of probabilities is easy, as the partition function cancels out and we are left with the exponential of an energy difference! The Metropolis-Hasting algorithm leverages this and also solves our state space problem by using a Markov chain to approximate the integral. So the idea is to build a Markov chain Xt that converges and has

as an invariant distribution, so that we can approximate the integral by

for large values of N.

But how do we construct a Markov chain that converges to a given distribution? The Metropolis Hastings approach to solve this works as follows.

The first thing that we do is to choose a proposal density q on our state space X, i.e. a measurable function

such that for each x, .

Then q defines a Markov chain, where the probability to transition into a measurable set A being at a point x is given by the integral

Of course this is not yet the Markov chain that we want – it has nothing to do with , so there is no reason it should converge to

. To fix this, we now adjust the kernel to incorporate the behaviour of

. For that purpose, define

This number is called the acceptance probability, and, as promised, it only contains ratios of probabilities, so that factors like the partition function cancel and do not have to be computed.

The Metropolis Hastings algorithm now proceeds as follows. We start with some arbitrary point x0. When the chain has arrived at xn, we first draw a candidate y for the next location from the proposal distribution . We now calculate

according to the formula above. We then accept the proposal with probability

, i.e. we draw a random sample U from a uniform distribution and accept if

. If the proposal is accepted, we set xn+1 = y, otherwise we set xn+1 = xn, i.e. we stay where we are.

Clearly, the xn are samples from a Markov chain, as the position at step xn only depends on the position at step xn-1. But is still appears to be a bit mysterious why this should work. To shed light on this, let us consider a case where the expressions above simplify a bit. So let us assume that the proposal density q is symmetric, i.e. that

This is the original Metropolis algorithm as proposed in [1]. If we also assume that and q are nowhere zero, the acceptance probability simplifies to

Thus we accept the proposal if with probability one. This is very similar to a random search for a global maximum – we start at some point x, choose a candidate for a point with higher value of

at random and proceed to this point. The major difference is that we also accept candidates with

with a non-zero probability. This allows the algorithm to escape a local maximum much better. Intuitively, the algorithm will still try to spend more time in regions with large values of

, as we would expect from an attempt to sample from the distribution

.

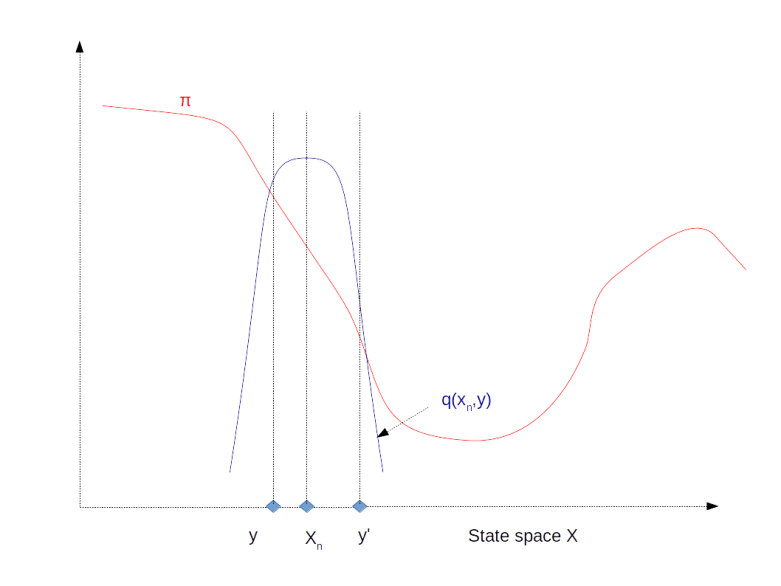

The image above illustrates this procedure. The red graph displays the distribution . If our algorithm is currently at step xn, the purpose is to move “up-hill”, i.e. to the left in our example. If we draw a point like y from q which goes already in the right directory, we will always accept this proposal and move to y. If, however, we draw a point like y’, at which

is smaller, we would accept this point with a non-zero probability. Thus if we have reached a local maximum like the one on the right hand side of the diagram, there is still a chance that we can escape from there and move towards the real maximum to the left.

In this form, the algorithm is extremely easy to implement. All we need is a function propose that creates the next proposal, and a function p that calculates the value of the probability density at some point. Then an implementation in Python is as follows.

import numpy as np

chain = []

X = 0

chain.append(X)

for n in range(args.steps):

Y = propose(X)

U = np.random.uniform()

alpha = p(Y) / p(X)

if (U <= alpha):

X = Y

chain.append(X)

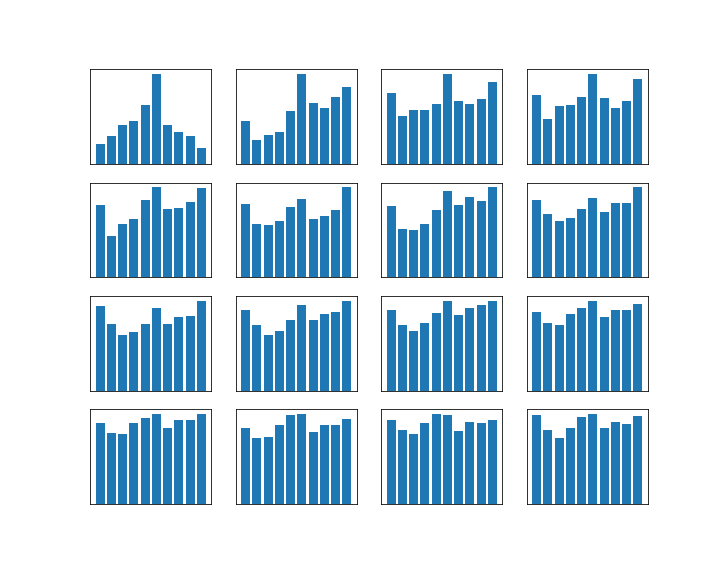

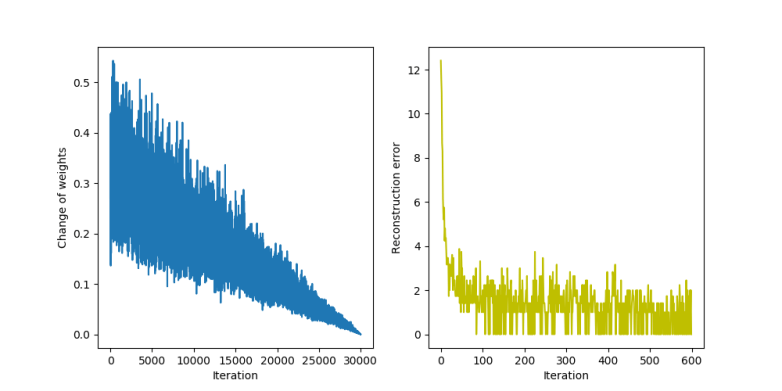

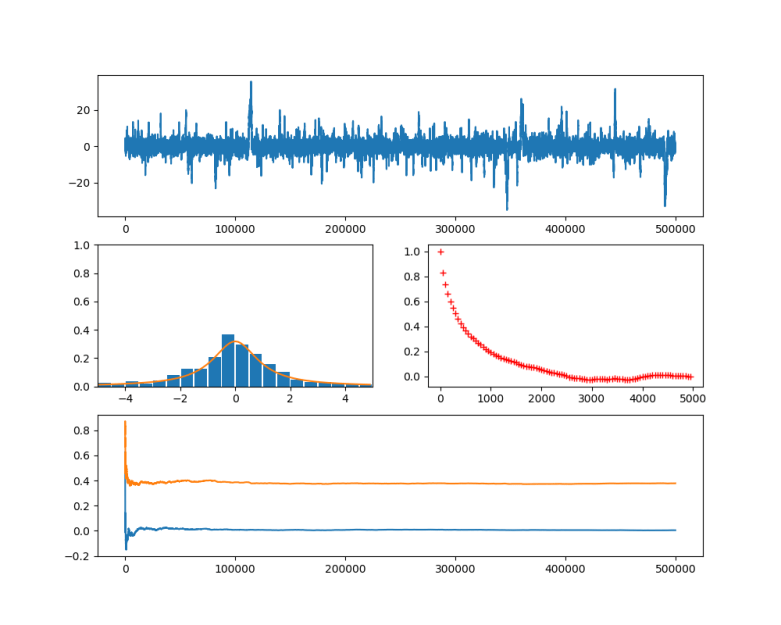

In the diagram below, this algorithm has been applied to a Cauchy distribution with mode zero and scale one, using a normal distribution with mean x and standard deviation 0.5 as a proposal for the next location. The chain was calculated for 500.000 steps. The diagram in the upper part shows the values of the chain during the simulation.

Then the first 100.000 steps were discarded and considered as "burn-in" time for the chain to stabilize. Out of the remaining 400.000 sample points, points where chosen with a distance of 500 time steps to obtain a sample which is approximately independent and identically distributed. This is called subsampling and typically not necessary for Monte Carlo integration (see [2], chapter 1 for a short discussion of the need of subsampling), but is done here for the sake of illustration. The resulting subsample is plotted as a histogramm in the lower left corner of the diagram. The yellow line is the actual probability density.

We see that after a few thousand steps, the chain converges, but continues to have spikes. However, the sampled distribution is very close to the sample generated by the Python standard method (which is to take the quotient of two independent samples from a standard normal distribution).

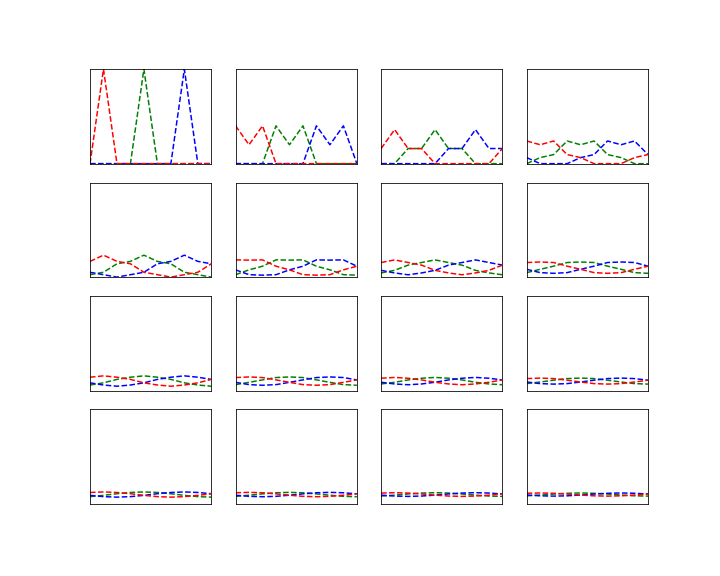

In the diagram at the bottom, I have displayed how the integral of two functions ( and

) approximated using the partial sums develops over time. We see that even though we still have huge spikes, the integral remains comparatively stable and converges already after a few thousand iterations. Even if we run the simulation only for 1000 steps, we already get close to the actual values zero (for

for symmetry reasons) and

(for

, obtained using the

scipy.integrate.quad integration routine).

In the second diagram in the middle row, I have plotted the autocorrelation versus the lag, as an indicator for the failure of the sample points to be independent. Recall that for two samples X and Y, the Pearson correlation coefficient is the number

where and

are the standard deviations of X and Y. In our case, given a lag, i.e. a number l less than the length of the chain, we can form two samples, one consisting of the points

and the second one consisting of the points of the shifted series

. The autocorrelation with lag l is then defined to be the correlation coefficient between these two series. In the diagram, we can see how the autocorrelation depends on the lag. We see that for a large lag, the autocorrelation becomes small, supporting our intuition that the series and the shifted series become independent. However, if we execute several simulation runs, we will also find that in some cases, the convergence of the autocorrelation is very slow, so care needs to be taken when trying to obtain a nearly independent sample from the chain.

In practice, the autocorrelation is probably not a good measure for the convergence of a Markov chain. It is important to keep in mind that obtaining an independent sample is not the point of the Markov chain – the real point is that even though the sample is autocorrelated, we can approximate expectation values fairly well. However, I have included the autocorrelation here for the sake of illustration.

This form of proposal distributions is not the only one that is commonly used. Another choice that appears often is called an independence sampler. Here the proposal distribution is chosen to be independent of the current location x of the chain. This gives us an algorithm that resembles the importance sampling method and also shares some of the difficulties associated with it – in my notes on Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, I have included a short discussion and a few examples. These notes also contain further references and a short discussion of why and when the Markov chain underlying a Metropolis-Hastings sampler converges.

Other variants of the algorithm work by updating – in a high-dimensional space – either only one variable at a time or entire blocks of variables that are known to be independent.

Finally, if we are dealing with a state space that can be split as a product , we can use the conditional probability given either x1 or x2 as a proposal distribution. Thus, we first fix x2, and draw a new value for x1 from the conditional probability for x1 given the current value of x2. Then we move to this new coordinate, fix x1, draw from the conditional distribution of x2 given x1 and set the new value of x2 accordingly. It can be shown (see for example [5]) that the acceptance probability is one in this case. So we end up with the Gibbs sampling algorithm that we have already used in the previous post on Ising models.

Monte Carlo sampling methods are a broad field, and even though this has already been a long post, we have only scratched the surface. I invite you to consult some of the references below and / or my notes for more details. As always, you will also find the sample code on GitHub and might want to play with this to reproduce the examples above and see how different settings impact the result.

In a certain sense, this post is the last post in the series on restricted Boltzmann machines, as it provides (at least some of) the mathematical background behind the Gibbs sampling approach that we used there. Boltzmann machines are examples for stochastic neuronal networks that can be applied to unsupervised learning, i.e. the allow a model to learn from a sample distribution without the need for labeled data. In the next few posts on machine learning, I will take a closer look at some other algorithms that can be used for unsupervised learning.

References

1. N. Metropolis,A.W. Rosenbluth, M.N. Rosenbluth, A.H. Teller, E. Teller, Equation of state calculation by fast computing machines, J. Chem. Phys. Vol. 21, No. 6 (1953), pp. 1087-1092

2. S. Brooks, A. Gelman, C.L. Jones,X.L. Meng (ed.), Handbook of Markov chain Monte Carlo, Chapman Hall / CRC Press, Boca Raton 2011

3. W.K. Hastings, Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications, Biometrika, Vol. 57 No. 1 (1970), pp. 97-109

R.M. Neal, Probabilistic inference using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, Technical Report CRG-TR-93-1, Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto, 1993

5. C.P. Robert, G. Casella, Monte Carlo Statistical Methods,

Springer, New York 1999