In most of our previous posts, we have discussed and used transformer networks that have been trained on a large set of data using teacher forcing. These models are good at completing a sentence with the most likely next token, but are not optimized for following instructions. Today, we will look at a specific family of networks that have been trained to tailor their response according to instructions – FLAN-T5 by Google.

If you ask a language model that has been trained on a large data set to complete a prompt that represents an instruction or a question, the result you will obtain is the most likely completion of the prompt. This, however, might not be the answer to your question – it could as well be another question or another instruction, as the model is simply trying to complete your prompt. For many applications, this is clearly not what we want.

One way around this is few-shot learning which basically means that you embed your instruction into a prompt that somehow resembles the first few lines of a document so that the answer that you expect is the most natural completion, giving the model a chance to solve your task by doing what it can do best, i.e. finding completions. This, however, is not really a satisfying approach and you might ask whether there is a way to fix the problem at training time, not at inference time. And in fact there is a method to train a model to recognize and follow instructions – instruction fine-tuning.

Most prominent models out there like GPT did undergo instruction fine tuning at some point. Today we will focus on a model series called FLAN-T5 which has been developed by Google and for which the exact details of the training process have been published in several papers (see the references). In addition, versions of the model without instruction fine tuning are available so that we can compare them with the fine-tuned versions.

In [1], instruction fine-tuning has been applied to LaMDA-PT, a decoder-only transformer model that Google had developed and trained earlier. In [2], the same method has been applied to T5, a second model series presented first in [3]. The resulting model series is known as FLAN-T5 and available on the Hugginface hub. So in this post, we will first discuss T5 and how it was trained and than explain the instruction fine tuning that turned T5 into FLAN-T5.

T5 – an encoder-decoder model

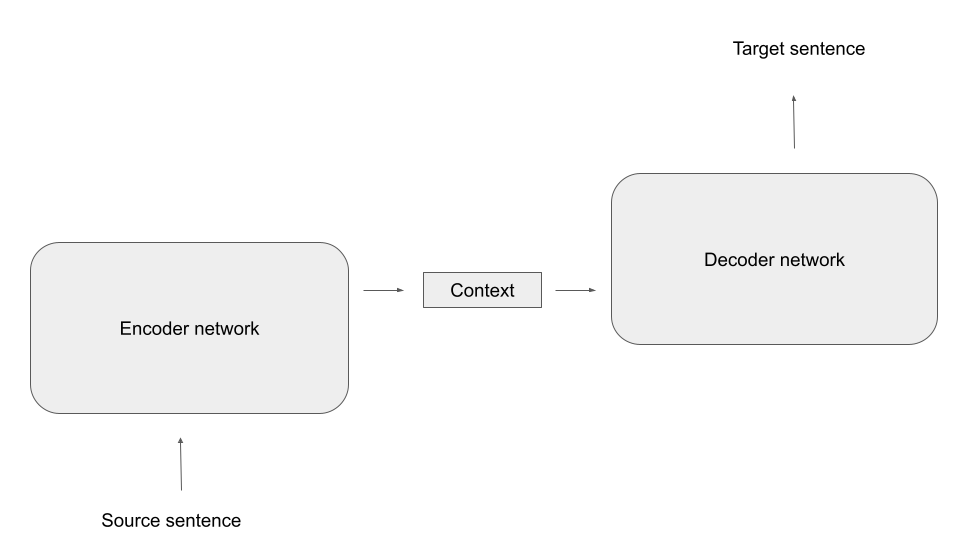

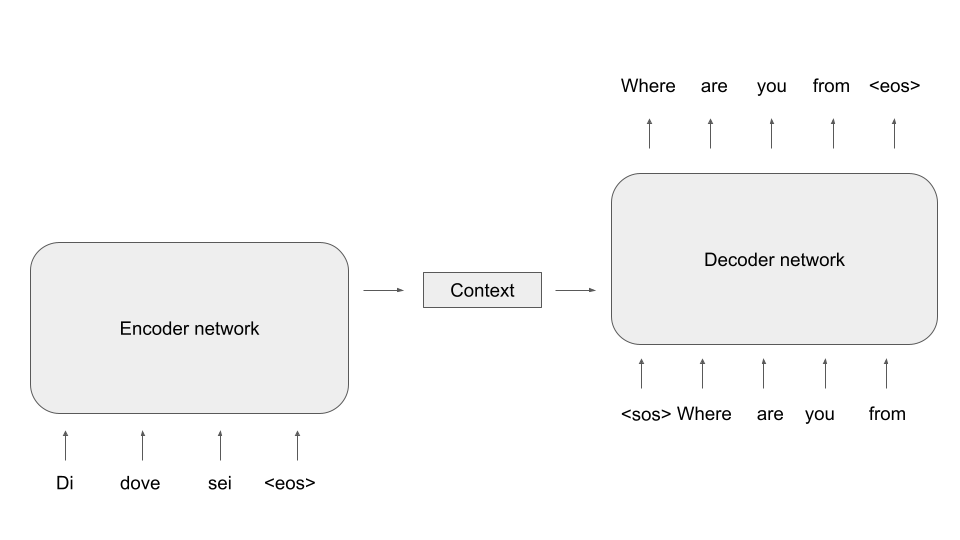

Other than most of the models we have played with so far, T5 is a full encoder-decoder model. If you have read my previous post on transformer blocks and encoder-decoder architectures, you might remember the following high-level overview of such an architecture.

For pre-training, Google did apply a method known as masking. This works as follows. Suppose your training data contains the following sentence:

The weather report predicted heavy rain for today

If we encode this using the the encoder used for training T5, we obtain the sequence of token

[37, 1969, 934, 15439, 2437, 3412, 21, 469, 1]

Note that the last token (with ID 1) is the end-of-sentence token that the tokenizer will append automatically to our input. We then select a few token in the sentence randomly and replace each of them with one of 100 special token called extra_id_NN, where NN is a number between 0 and 99. These token have IDs ranging from 32000 to 32099, where 32099 is extra token 0 and 32000 is extra token 99. After applying this procedure known as masking our sentence could look as follows

The weather report predicted heavy <extra_id_0> for today

or

[37, 1969, 934, 15439, 2437, 32099, 21, 469, 1]

We now train the decoder to output a list of the extra token used, followed by the masked word. So in our case, the target sequence for the decoder would be

<extra_id_0> rain

or, again including the end-of-sentence token

[32099, 3412, 1]

In other words, we ask our model to guess the word that has been replaced by the mask (this will remind you of the word2vec algorithm that I have presented in a previous post). To train the combination of encoder and decoder to reach that objective, we can again apply teacher forcing. For that purpose, we shift the labels to the right by one and append a special token called the decoder start token to the left (which, by the way, is identical to the padding token 0 in this case). So the input to the decoder is

[0, 32099, 3412]

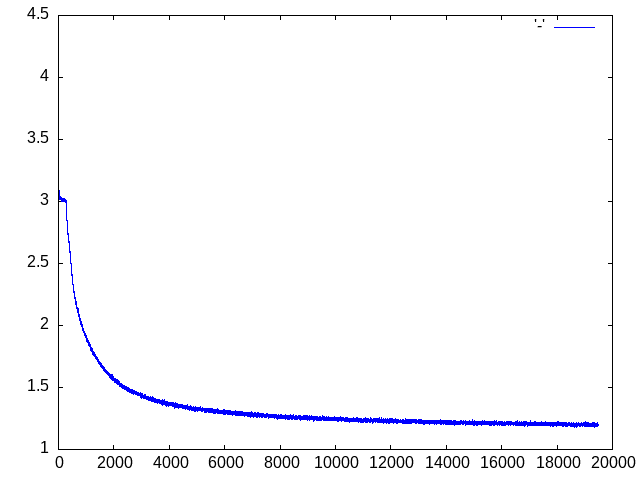

We then can calculate the cross-entropy loss between the decoder output and the labels above and apply gradient descent as usual. I have put together a notebook for this post that walks you through an example and that you can also run on Google Colab as usual.

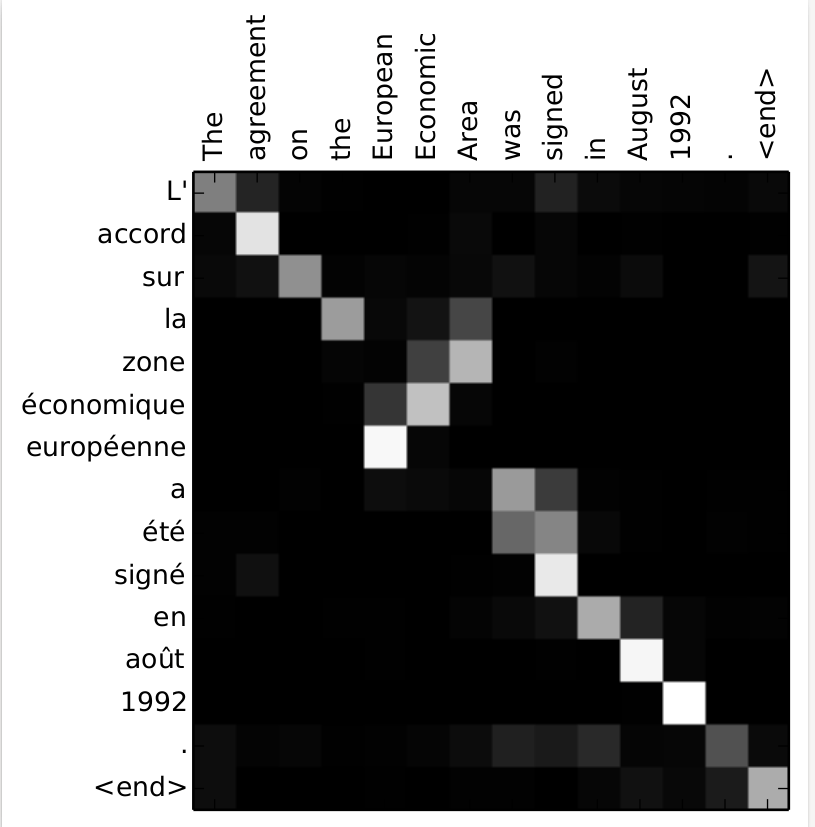

Pre-training using masking was the first stage in training T5. In a second stage, the model was fine-tuned on a set of downstream tasks. Examples for these tasks include translation, summarization, question answering and reasoning. For each task, the folks at Google defined a special format in which the model received the inputs and in which the output was expected. For translation, for instance, the task started with

“translate English to German: “

followed by the sentence to be translated, and the model was trained to reply with the correct translation. Another example is MNLI, which is a set of pairs of premise and hypothesis, and the model is supposed to answert with one word indicating whether a premise implies the hypothesis, is a contradiction to it or is neutral towards the hypothesis. In this case, the input is a sentence formatted as

“mnli premise: … premise goes here… hypothesis: … hypothesis goes here…

and the model is expected to answer with one of the three words “entailment”, “contradiction” or “neutral”. So all tasks are presented to the model as pure text and the outcome is expected to be pure text. My notebook contains a few examples of how this works.

From T5 to FLAN-T5

After the pre-training using masking and the fine-tuning, T5 is already a rather powerful model, but still is sometimes not able to deduce the correct task to perform. In the notebook for this post, I hit upon a very illustrative example. If we feed the sentence

Please answer the following question: what is the boiling temperature of water?

into the model, it will not reply with the actual boiling point of water. Instead, it will fall back to one of the tasks it has been trained on and will actually translate this to German instead of answering the question.

This is where instruction fine-tuning [2] comes into play. To teach the model to recognize instructions as such and to follow them, the T5 model was trained on a large number of additional tasks, phrased in natural language.

To obtain a larger number of tasks from the given dataset, the authors applied different templates to each task. If, for instance, we are given an MNLI task with a hypothesis H and a premise P, we could present this in several ways to the model, i.e. according to several templates. We could, for instance, turn the data point into natural language using the template

“Premise: P. Hypothesis: H. Does the premise entail the hypothesis?”

Or we could phrase this as

Based on the premise P, can we conclude that the hypothesis H is true?

By combining every data point from the used data set with a certain number of templates, a large dataset for the fine-tuning was obtained, and the model learned to deal with many different instructions referring to the same type of task, which hopefully would enable the model to infer the correct tasks for an unseen template at test time. As Google published the code to generate the data, you can take a look at the templates here.

Also note that the data contains some CoT (chain-of-thought) prompting, i.e. some of the instruction templates for reasoning tasks include phrases like “apply reasoning step-by-step” to prepare the model for later chain-of-thought prompting.

In the example in my notebook, the smallest FLAN-T5 model (i.e. T5 after this additional fine-tuning procedure) did at least recognize that the input is a question, but the reply (“a vapor”) is still not what we want. The large model does in fact reply with the correct answer (212 F).

Instruction fine-tuning has become the de-facto standard for large language models. The InstructGPT model from which ChatGPT and GPT-4 are derived, however, did undergo an additional phase of training – reinforcement learning from human feedback. This is a bit more complex, and as many posts on this exist which unfortunately do only scratch the surface I will dive deeper into this in the next post which will also conclude this series.

References

[1] J. Wei et al., Finetuned Language Models Are Zero-Shot Learners, arXiv:2109.01652

[2] H.W. Chung et al., Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models, arXiv:2210.11416

[3] C. Raffel et al., Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer, arXiv:1910.10683