Terraform is one of the most popular open source tools to quickly provision complex cloud based infrastructures, and Ansible is a powerful configuration management tool. Time to see how we can combine them to easily create cloud based infastructures in a defined state.

Terraform – a quick introduction

This post is not meant to be a full fledged Terraform tutorial, and there are many sources out there on the web that you can use to get familiar with it quickly (the excellent documentation itself, for instance, which is quite readable and quickly gets to the point). In this section, we will only review a few basic facts about Terraform that we will need.

When using Terraform, you declare the to-be state of your infrastructure in a set of resource definitions using a declarative language known as HCL (Hashicorp configuration language). Each resource that you declare has a type, which could be something like aws_instance or packet_device, which needs to match a type supported by a Terraform provider, and a name that you will use to reference your resource. Here is an example that defines a Packet.net server.

resource "packet_device" "web1" {

hostname = "tf.coreos2"

plan = "t1.small.x86"

facilities = ["ewr1"]

operating_system = "coreos_stable"

billing_cycle = "hourly"

project_id = "${local.project_id}"

}

In addition to resources, there are a few other things that a typical configuration will contain. First, there are providers, which are an abstraction for the actual cloud platform. Each provider is enabling a certain set of resource types and needs to be declared so that Terraform is able to download the respective plugin. Then, there are variables that you can declare and use in your resource definitions. In addition, Terraform allows you to define data sources, which represent queries against the cloud providers API to gather certain facts and store them into variables for later use. And there are objects called provisioners that allow you to run certain actions on the local machine or on the machine just provisioned when a resource is created or destroyed.

An important difference between Terraform and Ansible is that Terraform also maintains a state. Essentially, the state keeps track of the state of the infrastructure and maps the Terraform resources to actual resources on the platform. If, for instance, you define a EC2 instance my-machine as a Terraform resource and ask Terraform to provision that machine, Terraform will capture the EC2 instance ID of this machine and store it as part of its state. This allows Terraform to link the abstract resource to the actual EC2 instance that has been created.

State can be stored locally, but this is not only dangerous, as a locally stored state is not protected against loss, but also makes working in teams difficult as everybody who is using Terraform to maintain a certain infrastructure needs access to the state. Thereform, Terraform offers backends that allow you to store state remotely, including PostgreSQL, S3, Artifactory, GCS, etcd or a Hashicorp managed service called Terraform cloud.

A first example – Terraform and DigitalOcean

In this section, we will see how Terraform can be used to provision a droplet on DigitalOcean. First, obviously, we need to install Terraform. Terraform comes as a single binary in a zipped file. Thus installation is very easy. Just navigate to the download page, get the URL for your OS, run the download and unzip the file. For Linux, for instance, this would be

wget https://releases.hashicorp.com/terraform/0.12.10/terraform_0.12.10_linux_amd64.zip unzip terraform_0.12.10_linux_amd64.zip

Then move the result executable somewhere into your path. Next, we will prepare a simple Terraform resource definition. By convention, Terraform expects resource definitions in files with the extension .tf. Thus, let us create a file droplet.tf with the following content.

# The DigitalOcean oauth token. We will set this with the

# -var="do_token=..." command line option

variable "do_token" {}

# The DigitalOcean provider

provider "digitalocean" {

token = "${var.do_token}"

}

# Create a droplet

resource "digitalocean_droplet" "droplet0" {

image = "ubuntu-18-04-x64"

name = "droplet0"

region = "fra1"

size = "s-1vcpu-1gb"

ssh_keys = []

}

When you run Terraform in a directory, it will pick up all files with that extension that are present in this directory (Terraform treats directories as modules with a hierarchy starting with the root module). In our example, we make a reference to the DigitalOcean provider, passing the DigitalOcean token as an argument, and then declare one resource of type digitalocean_droplet called droplet0

Let us try this out. When we use a provider for the first time, we need to initialize this provider, which is done by running (in the directory where your resource definitions are located)

terraform init

This will detect all required providers and download the respective plugins. Next, we can ask Terraform to create a plan of the changes necessary to realize the to-be state described in the resource definition. To see this in action, run

terraform plan -var="do_token=$DO_TOKEN"

Note that we use the command line switch -var to define the value of the variable do_token which we reference in our resource definition to allow Terraform to authorize against the DigitalOcean API. Here, we assume that you have stored the DigitalOcean token in an environment variable called DO_TOKEN.

When we are happy with the output, we can now finally ask Terraform to actually apply the changes. Again, we need to provide the DigitalOcean token. In addition, we also use the switch -auto-approve, otherwise Terraform would ask us for a confirmation before the changes are actually applied.

terraform apply -auto-approve -var="do_token=$DO_TOKEN"

If you have a DigitalOcean console open in parallel, you can see that a droplet is actually being created, and after less than a minute, Terraform will complete and inform you that a new resource has been created.

We have mentioned above that Terraform maintains a state, and it is instructive to inspect this state after a resource has been created. As we have not specified a backend, Terraform will keep the state locally in a file called terraform.tfstate that you can look at manually. Alternatively, you can also use

terraform state pull

You will see an array resources with – in our case – only one entry, representing our droplet. We see the name and the type of the resource as specified in the droplet.tf file, followed by a list of instances that contains the (provider specific) details of the actual instances that Terraform has stored.

When we are done, we can also use Terraform to destroy our resources again. Simply run

terraform destroy -auto-approve -var="do_token=$DO_TOKEN"

and watch how Terraform brings down the droplet again (and removes it from the state).

Now let us improve our simple resource definition a bit. Our setup so far did not provision any SSH keys, so to log into the machine, we would have to use the SSH password that DigitalOcean will have mailed you. To avoid this, we again need to specify an SSH key name and to get the corresponding SSH key ID. First, we define a Terraform variable that will contain the key name and add it to our droplet.tf file.

variable "ssh_key_name" {

type = string

default = "do-default-key"

}

This definition has three parts. Following the keyword variable, we first specify the variable name. We then tell Terraform that this is a string, and we provide a default. As before, we could override this default using the switch -var on the command line.

Next, we need to retrieve the ID of the key. The DigitalOcean plugin provides the required functionality as a data source. To use it, add the following to our resource definition file.

data "digitalocean_ssh_key" "ssh_key_data" {

name = "${var.ssh_key_name}"

}

Here, we define a data source called ssh_key_data. The only argument to that data source is the name of the SSH key. To provide it, we use the template mechanism that Terraform provides to expand variables inside a string to refer to our previously defined variable.

The data source will then use the DigitalOcean API to retrieve the key details and store them in memory. We can now access the SSH key to add it to the droplet resource definition as follows.

# Create a droplet

resource "digitalocean_droplet" "droplet0" {

...

ssh_keys = [ data.digitalocean_ssh_key.ssh_key_data.id ]

}

Note that the variable reference consists of the keyword data to indicate that is has been populated by a data source, followed by the type and the name of the data source and finally the attribute that we refer to. If you now run the example again, we will get a machine with an SSH key so that we can access it via SSH as usual (run terraform state pull to get the IP address).

Having to extract the IP manually from the state file is not nice, it would be much more convenient if we could ask the Terraform to somehow provide this as an output. So let us add the following section to our file.

output "instance_ip_addr" {

value = digitalocean_droplet.droplet0.ipv4_address

}

Here, we define an output called instance_ip_addr and populate it by referring to a data item which is exported by the DigitalOcean plugin. Each resource type will have its own list of exported variables which you can find in the documentation, and you can only refer to one of these variables. If we now run Terraform again, it will print the output upon completion.

We can also create more than one instance at a time by adding the keyword count to the resource definition. When defining the output, we will now have to refer to the instances as an array using the splat expression syntax to refer to an entire array. It is also advisible to move the entire instance configuration into variables and to split out variable definitions into a separate file.

Using Terraform with a non-local state

Using Terraform with a local state can be problematic – it could easily get lost or overwritten and makes working in a team or at different locations difficult. Therefore, let us quickly look at an example to set up Terraform with non-local state. Among the many available backends, we will use PostgreSQL.

Thanks to docker, it is very easy to bring up a local PostgreSQL instance. Simply run

docker run --name tf-backend -e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=my-secret-password -d postgres

Note that we do not map the PostgreSQL port here for security reasons, so we will need to figure out the IP of the resulting Docker container and use it in the Terraform configuration. The IP can be retrieved with the following command.

docker inspect tf-backend | jq -r '.[0].NetworkSettings.IPAddress'

In my example, the Docker container is running at 172.17.0.2. Next, we will have to create a database for the Terraform backend. Assuming that you have the required client packages installed, run

createdb --host=172.17.0.2 --username=postgres terraform_backend

and enter the password my-secret-password specified above when starting the Docker container. We will use the PostgreSQL superuser for our example, in a real life example you would of course first create your own user for Terraform and use it going forward.

Next, we add the backend definition to our Terraform configuration using the following section.

# The backend - we use PostgreSQL.

terraform {

backend "pg" {

}

}

You might expect that we also need to provide the location of the database (i.e. a connection string) and credentials. In fact, we could do this, but this would imply that the credentials which are part of the connection string would be present in the file in clear text. We therefore use a partial configuration and later supply the missing data on the command line.

Finally, we have to re-run terraform init to make the new backend known to Terraform and create a new workspace. Terraform will detect the change and even offer you to automatically migrate the state into the new backend.

terraform init -backend-config="conn_str=postgres://postgres:my-secret-password@172.17.0.2/terraform_backend?sslmode=disable" terraform workspace new default

Be careful – as our database is running in a container with ephemeral storage, the state will be lost when we destroy the container! In our case, this would not be a desaster, as we would still be able to control our small playground environment manually. Still, it is a good idea to tag all your servers so that you can easily identify the servers managed by Terraform. If you intend to use Terraform more often, you might also want to spin up a local PostgreSQL server outside of a container (here is a short Ansible script that will do this for you and create a default user terraform with password being equal to the user name). Note that with a non-local state, Terraform will still store a reference to your state locally (look at the directory .terraform), so that when you work from a different directory, you will have to run the init command again. Also note that this will store your database credentials locally on disk in clear text.

Combining Terraform and Ansible

After this very short introduction into Terraform, let us now discuss how we can combine Terraform to manage our cloud environment with Ansible to manage the machines. Of course there are many different options, and I have not even tried to create an exhaustive list. Here are the options that I did consider.

First, you could operate Terraform and Ansible independently and use a dynamic inventory. Thus, you would have some Terraform templates and some Ansible playbooks and, when you need to verify or update your infrastructure, first run Terraform and then Ansible. The Ansible playbooks would use provider-specific inventory scripts to build a dynamic inventory and operate on this. This setup is simple and allows you to manage the Terraform configuration and your playbooks without any direct dependencies.

However, there is a potential loss of information when working with inventory scripts. Suppose, for instance, that you want to bring up a configuration with two web servers and two database servers. In a Terraform template, you would then typically have a resource “web” with two instances and a resource “db” with two instances. Correspondingly, you would want groups “web” and “db” in your inventory. If you use inventory scripts, there is no direct link between Terraform resources and cloud resources, and you would have to use tags to provide that link. Also, things easily get a bit more complicated if your configuration uses more than one cloud provider. Still, this is a robust method that seems to have some practical uses.

A second potential approach is to use Terraform provisioners to run Ansible scripts on each provisioned resource. If you decide to go down this road, keep in mind that provisioners only run when a resource is created or destroyed, not when it changes. If, for instance, you change your playbooks and simply run Terraform again, it will not trigger any provisioners and the changed playbooks will not apply. There are approaches to deal with this, for instance null resources, but this is difficult to control and the Terraform documentation itself does not advocate the use of provisioners.

Next, you could think about parsing the Terraform state. Your primary workflow would be coded into an Ansible playbook. When you execute this playbook, there is a play or task which reads out the Terraform state and uses this information to build a dynamic inventory with the add_host module. There are a couple of Python scripts out there that do exactly this. Unfortunately, the structure of the state is still provider specific, a DigitalOcean droplet is stored in a structure that is different from the structure used for a AWS EC2 instance. Thus, at least the script that you use for parsing the state is still provider specific. And of course there are potential race conditions when you parse the state while someone else might modify it, so you have to think about locking the state while working with it.

Finally, you could combine Terraform and Ansible with a tool like Packer to create immutable infrastructures. With this approach, you would use Packer to create images, supported maybe by Ansible as a provisioner. You would then use Terraform to bring up an infrastructure using this image, and would try to restrict the in-place configurations to an absolute minimum.

The approach that I have explored for this post is not to parse the state, but to trigger Terraform from Ansible and to parse the Terraform output. Thus our playbook will work as follows.

- Use the Terraform module that comes with Ansible to run a Terraform template that describes the infrastructure

- Within the Terraform template, create an output that contains the inventory data in a provider independent JSON format

- Back in Ansible, parse that output and use add_host to build a corresponding dynamic inventory

- Continue with the actual provisioning tasks per server in the playbook

Here, the provider specific part is hidden in the Terraform template (which is already provider specific by design), where the data passed back to Ansible and the Ansible playbook at least has a chance to be provider agnostic.

Similar to a dynamic inventory script, we have to reach out to the cloud provider once to get the current state. In fact, behind the scenes, the Terraform module will always run a terraform plan and then check its output to see whether there is any change. If there is a change, it will run terraform apply and return its output, otherwise it will fall back to the output from the last run stored in the state by running terraform output. This also implies that there is again a certain danger of running into race conditions if someone else runs Terraform in parallel, as we release the lock on the Terraform state once this phase has completed.

Note that this approach has a few consequences. First, there is a structural coupling between Terraform and Ansible. Whoever is coding the Terraform part needs to prepare an output in a defined structure so that Ansible is happy. Also the user running Ansible needs to have the necessary credentials to run Terraform and access the Terraform state. In addition, Terraform will be invoked every time when you run the Ansible playbook, which, especially for larger infrastructures, slows down the processing a bit (looking at the source code of the Terraform module, it would probably be easy to add a switch so that only terraform output is run, which should provide a significant speedup).

Getting and running the sample code

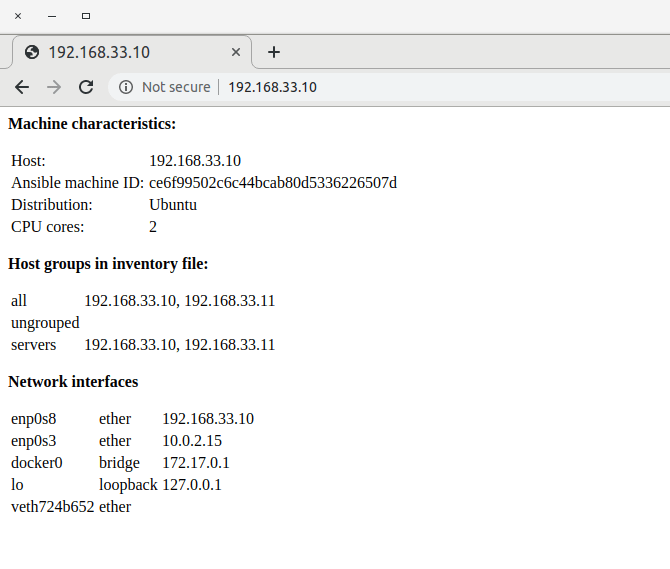

Let us now take a look at a sample implementation of this idea which I have uploaded into my Github repository. The code is organized into a collection of Terraform modules and Ansible roles. The example will bring up two web servers on DigitalOcean and two database servers on AWS EC2.

Let us first discuss the Terraform part. There are two modules involved, one module that will create a droplet on DigitalOcean and one module that will create an EC2 instance. Each module returns, as an output, a data structure that contains one entry for each server, and each entry contains the inventory data for that server, for instance

inventory = [

{

"ansible_ssh_user" = "root"

"groups" = "['web']"

"ip" = "46.101.162.72"

"name" = "web0"

"private_key_file" = "~/.ssh/do-default-key"

},

...

This structure can easily be assembled using Terraforms for-expressions. Assuming that you have defined a DigitalOcean resource for your droplets, for instance, the corresponding code for DigitalOcean is

output "inventory" {

value = [for s in digitalocean_droplet.droplet[*] : {

# the Ansible groups to which we will assign the server

"groups" : var.ansibleGroups,

"name" : "${s.name}",

"ip" : "${s.ipv4_address}",

"ansible_ssh_user" : "root",

"private_key_file" : "${var.do_ssh_private_key_file}"

} ]

}

The EC2 module is structured similarly and delivers output in the same format (note that there is no name exported by the AWS provider, but we can use a tag to capture and access the name).

In the main.tf file, we then simply invoke each of the modules, concatenate their outputs and return this as Terraform output.

This output is then processed by the Ansible role terraform. Here, we simply iterate over the output (which is in JSON format and therefore recognized by Ansible as a data structure, not just a string), and for each item, we create a corresponding entry in the dynamic inventory using add_host.

The other roles in the repository are straightforward, maybe with one exception – the role sshConfig which will add entries for all provisioned hosts in an SSH configuration file ~/.ssh/ansible_created_config and include this file in the users main SSH configuration file. This is not necessary for things to work, but will allow you to simply type something like

ssh db0

to access the first database server, without having to specify IP address, user and private key file.

A note on SSH. When I played with this, I hit upon this problem with the Gnome keyring daemon. The daemon adds identities to your SSH agent, which are attempted every time Ansible tries to log into one of the machines. If you work with more than a few SSH identities, we will therefore exceed the number of failed SSH login attempts configured in the Ubuntu image, and will not be able to connect any more. The solution for me was to disable the Gnome keyring at startup.

In order to run the sample, you will first have to prepare a few credentials. We assume that

- You have AWS credentials set up to access the AWS API

- The DigitalOcean API key is stored in the environment variable DO_TOKEN

- There is a private key file ~/.ssh/ec2-default-key.pem matching an SSH key on EC2 called ec2-default-key

- Similarly, there is a private key file ~/.ssh/do-default-key that belongs to a public key uploaded to DigitalOcean as do-default-key

- There is a private / public SSH key pair ~/.ssh/default-user-key[.pub] which we will use to set up an SSH enabled default user on each machine

We also assume that you have a Terraform backend up and running and have run terraform init to connect to this backend.

To run the examples, you can then use the following steps.

git clone https://github.com/christianb93/ansible-samples cd ansible-samples/terraform terraform init ansible-playbook site.yaml

The extra invocation of terraform init is required because we introduce two new modules that Terraform needs to pre-load, and because you might not have the provider plugins for DigitalOcean and AWS on your machine. If everything works, you will have a fully provisioned environment with two servers on DigitalOcean with Apache2 installed and two servers on EC2 with PostgreSQL installed up and running in a few minutes. If you are done, do not forget to shut down everything again by running

terraform destroy -var="do_token=$DO_TOKEN"

Also I highly recommend to use the DigitalOcean and AWS console to manually check that no servers are left running to avoid unnecessary cost and to be prepared for the case that your state is out-of-sync.