Mining is a challenge – a miner has to solve a mathematical puzzle to create a valid block and is rewarded with a certain bitcoin amount (12.5 at the time of writing) for investing electricity and computing power. But technology evolves, and the whole mining process would be pointless if the challenge could not be adapted dynamically to make sure that mining power and the difficulty of the challenge stay in balance. In this post, we will look in a bit more detail into this mechanism.

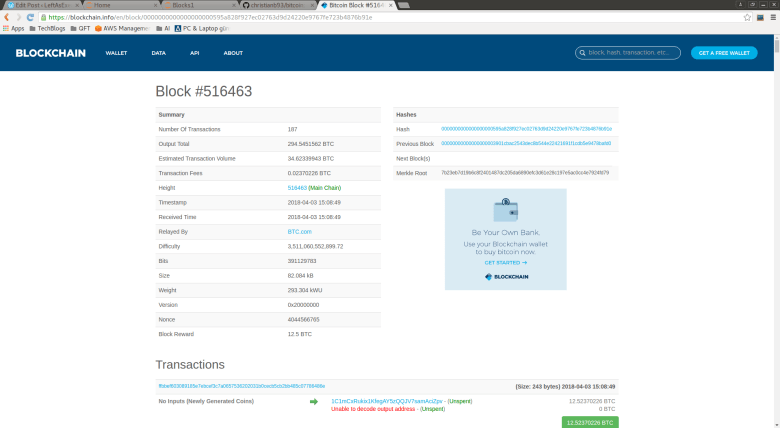

We have already seen that a block header contains – at character 144 – a four byte long number that is called bits in the source code and which seems to be related to the difficulty. As an example, let us take the block with the hash

0000000000000000000595a828f927ec02763d9d24220e9767fe723b4876b91e

You can get a human readable description of the block at this URL and will see the following output.

This output has a field bits that has the value 391129783. If you convert this into a hexadecimal string, you obtain 0x17502ab7, using for instance Pythons hex function. Now this function will give you the big-endian representation of the integer value. To convert to little endian as it can be found in the serialized format of a bitcoin block, you have to reverse the order byte wise and get b72a5017. If you now display the raw format of the block using this link and search for that string, you will actually find it at character 144 at expected.

Now on the screenshot above, you also see the difficulty displayed, which is a floating point number and is 3511060552899.72 in this case. How is that difficulty related to the bits?

As so often, we can find the answer in the bitcoin core source code, starting at the JSON RPC interface. So let us look at the function blockheaderToJSON in rpc/blockchain.cpp that is responsible for transforming a block in the internal representation into a human readable JSON format. Here we find the line

result.push_back(Pair("difficulty", GetDifficulty(blockindex)));

So let us visit the function GetDifficulty that we find in the same file, actually just a few lines up. Here we see that the bits are actually split into two parts. The first part, let me call this the size is just the value of the top 8 bits. The second part, the value of remaining 24 bits, is called the coefficient. Then the difficulty is calculated by dividing the constant 0xFFFF by the coefficient and shifting by 29 – size bits, i.e. according to the formula

In Python, we can therefore use the following two lines to extract the difficulty from a block header in raw format.

nBits = int.from_bytes(bytes.fromhex(raw[144:152]), "little") difficulty = 256**(29 - (nBits >> 24))*(65535.0 / ((float)(nBits & 0xFFFFFF)))

If you try this out for the transaction above, you will get 3511060552899.7197. Up to rounding after the second digit after the decimal point, this is exactly what we also see on the screenshot of blockchain.info. So far this is quite nice…

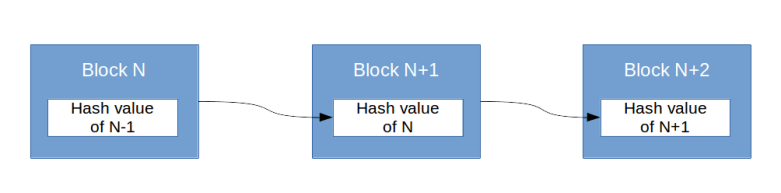

However, we are not yet done – this is not the only way to represent the difficulty. The second quantity we need to understand is the target. Recall that the mathematical puzzle that a miner needs to solve is to produce a block with a hash that does not exceed a given number. This number is the target. The lower the target, the smaller the range of 256 bit numbers that do not exceed the target, and the more difficult to solve that puzzle. So a low target implies high difficulty and vice versa.

In fact, there are two target values. One target is part of every block and stored in the bits field – we will see in a minute how this works. The second target is a global target that all nodes in the bitcoin network share – this value is updated independently by each node, but based on the same data (the blockchain) and the same rules so that they arrive at the same conclusion. A block considered valid if solves the mathematical puzzle according to the target which is stored in itself and if, in addition, this target matches the global target.

To understand how this works and the exact relation between target and difficulty, it is again useful to take a look at the source code. The relevant function is the function CheckProofOfWork in pow.cpp which is surprisingly short.

bool CheckProofOfWork(uint256 hash, unsigned int nBits, const Consensus::Params& params)

{

bool fNegative;

bool fOverflow;

arith_uint256 bnTarget;

bnTarget.SetCompact(nBits, &fNegative, &fOverflow);

// Check range

if (fNegative || bnTarget == 0 || fOverflow || bnTarget > UintToArith256(params.powLimit))

return false;

// Check proof of work matches claimed amount

if (UintToArith256(hash) > bnTarget)

return false;

return true;

}

Let us try to understand what is going on here. First, a new 256 bit integer bnTarget is instantiated and populated from the bits (that are taken from the block) using the method SetCompact. In addition to a range check, it is then checked that the hash of the block does not exceed the target – this the mathematical puzzle that we need to solve.

The second check – verifying that the target in the block matches the global target – happens in validation.cpp in the function ContextualCheckBlockHeader. At this point, the function GetNextWorkRequired required is called which determines the correct value for the global target. Then this is compared to the bits field in the block and the validation fails if they do not match. So for a block to be accepted as valid, the miner needs to:

- Actually solve the puzzle, i.e. provide a block with a hash value equal to or smaller than the current global target

- Include this target as bits in the generated block

This leaves a couple of questions open. First, we still have to understand how the second step – encoding the target in the bits field – works. And then we have to understand how the global target is determined.

Let us start with the first question. We have seen that the target is determined from the bits using the SetCompact method of the class uint256. This function is in fact quite similar to GetDifficulty studied before. Ignoring overflows and signs for a moment, we find that the target is determined from the bits as

If we compare this to the formula for the difficulty that we have obtained earlier, we find that there a simple relation between them:

where std_target is the target corresponding to difficulty 1.0 and given by 0xFFFF shifted by 208 bits to the left, i.e. by 0xFFFF with 52 trailing zeros. So up to a constant, target and difficulty are simply inverse to each other.

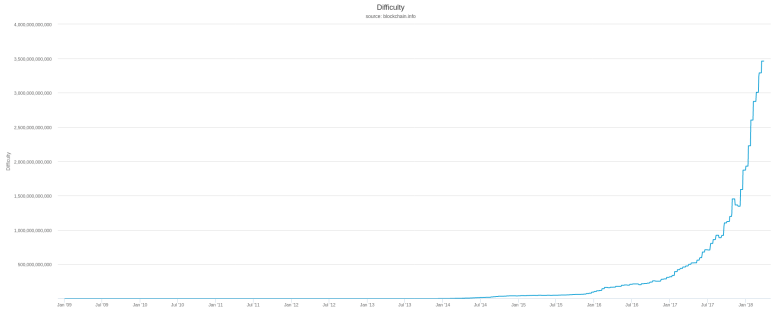

Now let us turn to the second question – how can the nodes agree on the correct global target? To see this, we need to look at the function GetNextWorkRequired. In most cases, this function will simply return the bits field of the current last block in the blockchain. However, every 2016 blocks, it will adjust the difficulty according to the following rule.

First, it will use the time stamps in the block to calculate how much time has passed since the block which is 2016 blocks back in the chain has been created – this value is called the actual time span. Then, this is compared with the target time span which is two weeks. The new target is then obtained by the formula (ignoring some range checks that are done to avoid too massive jumps)

Thus if the actual time span is smaller than the target time span, indicating that the mining power is too high and therefore the rate of block creation is too high, the target decreases and consequently the difficulty increases. This should make it more difficult for the miners to create new blocks and the block creation rate should go down again. Similarly, if the difficulty is too high, this mechanism will make sure that it is adjusted downwards. Thus the target rate is 2016 blocks being created in two weeks, i.e. 336 hours, which is a rate of six blocks per hours, i.e. 10 minutes for one block.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that there is lower limit for the difficulty, corresponding to a higher limit for the target. This limit is (as most of the other parameters that we have discussed) contained in chainparams.cpp and specific for the three networks main, net and regtest. For instance, for the main network, this is

consensus.powLimit = uint256S("00000000ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff");

whereas the same parameter for the regression testing network is

consensus.powLimit = uint256S("7fffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff");

This, together with the target of the genesis block (which determines the target for the first 2016 blocks) (bits = 0x207fffff ) determines the initial difficulty in a regression test network. Let us verify this (I knew I would somehow find a reason to add a notebook to this post…)

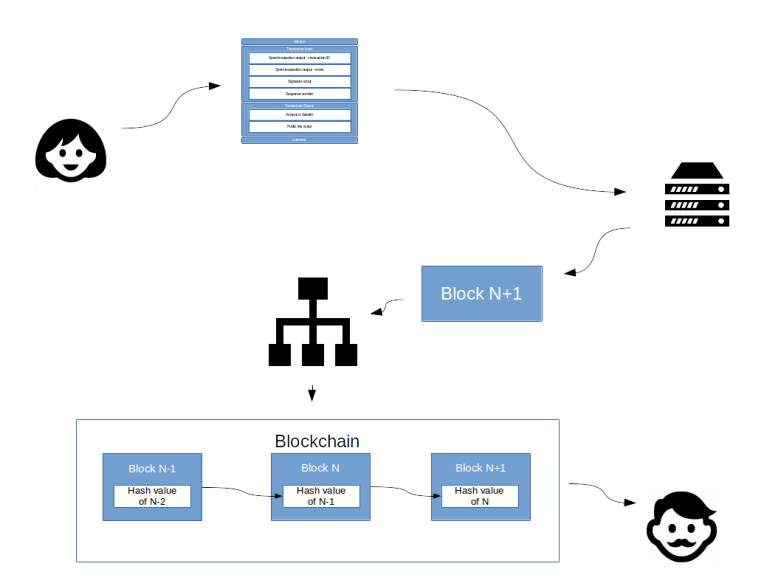

We are now well equipped to move towards our final project in this series – building a Python based miner. The last thing that we need to understand is how the miner operates and communicates with the bitcoin server, and this will be the topic of the next post.